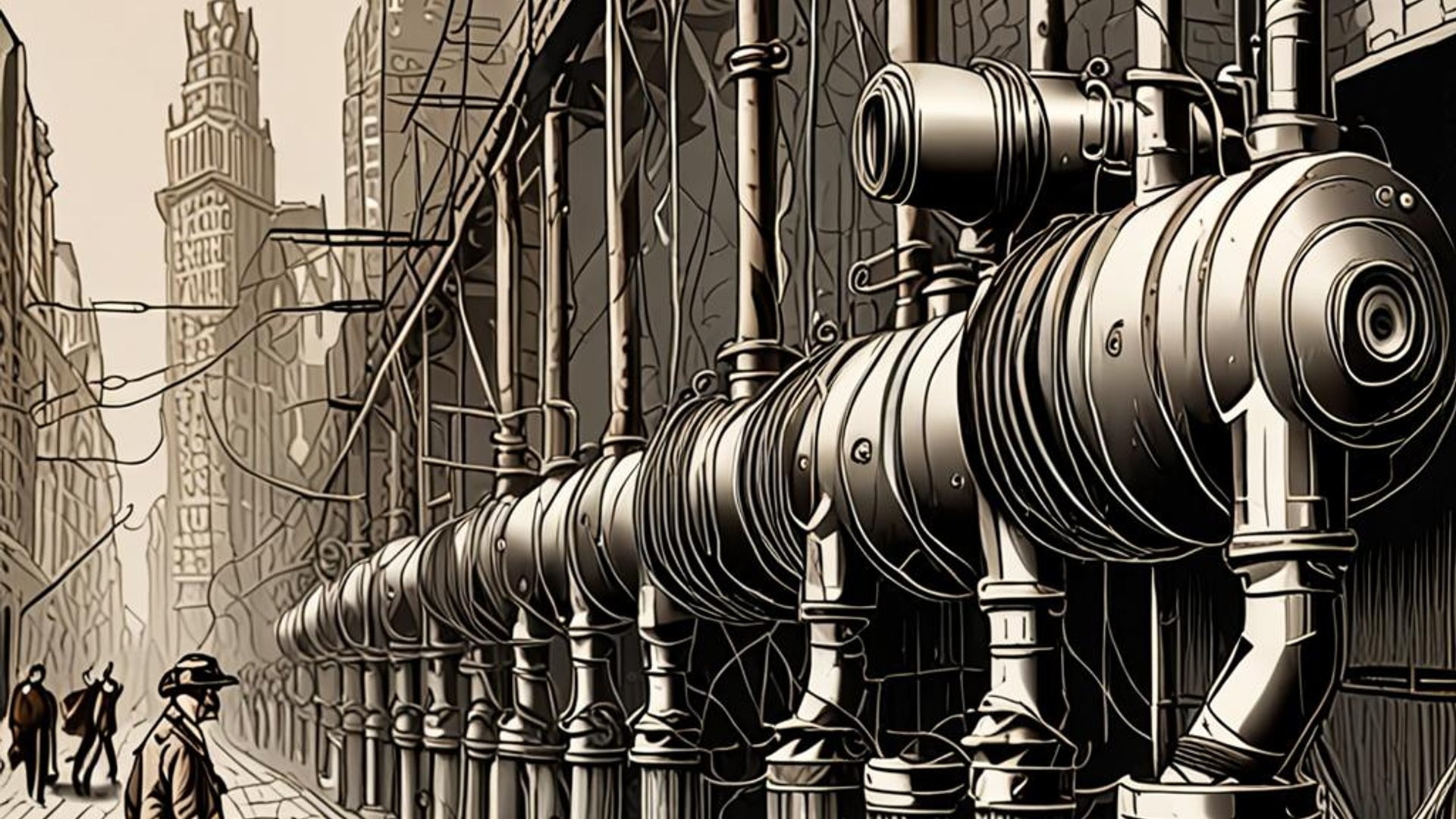

Infrastructure is never neutral. The pipes beneath our streets, the power lines overhead, the data cables crossing continents—these are not merely technical systems. They are political architectures that determine who has access, who profits, and who governs.

The Grid as Government

When we speak of "the grid," we usually mean the electrical network. But the grid is also a map of authority. Control the power supply, and you control economic activity, public safety, and daily life.

In the United States, this control is fragmented: municipal utilities, investor-owned companies, regional cooperatives, and federal agencies all stake claims. This patchwork reflects deeper questions about federalism, privatization, and the commons.

Consider Texas. The state operates its own electrical grid—ERCOT—deliberately isolated from federal oversight. This is infrastructure as political statement: a declaration of sovereignty, a bet on deregulation.

When Winter Storm Uri struck in February 2021, that bet revealed its cost. Millions lost power. Hundreds died. The infrastructure failed not due to technical inadequacy alone, but because of policy choices: minimal winterization requirements, profit-driven market structures, resistance to interstate connection.

Pipelines and Place

Pipelines, too, are political instruments. The Dakota Access Pipeline, the Keystone XL, the proposed Mountain Valley—each represents contested terrain, literally and figuratively.

These routes do not emerge from engineering necessity. They follow paths of least political resistance: through Indigenous land, through low-income communities, through areas with limited lobbying power.

The infrastructure of extraction is designed to be invisible to those who benefit from it, visible only to those who bear its burdens. This is spatial injustice encoded in steel and concrete.

Data Infrastructure

The newest layer of infrastructure—digital—is perhaps the most politically consequential. Who owns the fiber optic cables? Where are the server farms? Who regulates data flows?

Amazon Web Services hosts much of the federal government's cloud infrastructure. Google processes billions of searches. Facebook (Meta) mediates social connection for billions. These are not mere platforms; they are utilities, unregulated and unaccountable.

As we debate antitrust enforcement and Section 230, we are really debating governance itself: Can democratic institutions oversee private infrastructure that shapes public life?

Reclaiming Infrastructure

Infrastructure reveals and reinforces power relations. But it can also be a site of democratic renewal.

Community solar programs allow collective ownership of energy generation. Municipal broadband networks assert public control over digital infrastructure. Participatory budgeting lets residents decide which streets get repaved, which parks get renovated.

These are not utopian gestures. They are practical assertions that infrastructure belongs to the public, that systems can be governed democratically, that the physical and the political are inseparable.

Conclusion

To understand American politics, look at its infrastructure. The pipes, wires, and cables tell stories of who matters and who doesn't, who decides and who endures.

Changing politics means changing infrastructure. Not just building more efficiently, but building more equitably. Not just maintaining what exists, but reimagining what's possible.

Infrastructure is destiny. Let's choose it wisely.

This article is part of our Governance & Power series, examining how physical systems shape political realities. Next in the series: "The Zoning Origins of Urban Inequality."